Clearing House Certificates

History

In the decade before the Clearing House was founded, banking had become increasingly complex. From 1849 to 1853 –years highlighted by the California gold rush and construction of a national railroad system–the number of New York banks increased from 24 to 57. Settlement procedures were unsophisticated, with banks settling their accounts by employing porters to travel from bank to bank to exchange checks for bags of coin, or “specie.” As the number of banks grew, exchanges became a daily event. The official reckoning of accounts, however, did not take place until Fridays, often resulting in record keeping errors and encouraging abuses. Each day, the porters would gather on the steps of one of the Wall Street banks for their “Porters’ Exchange.”

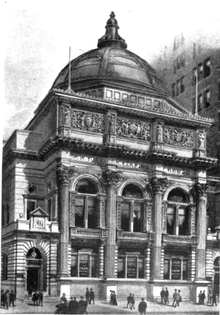

In 1853, a bank bookkeeper named George D. Lyman proposed in an article that banks send and receive checks at a central office. There was a positive response and The New York Clearing House was organized officially on October 4 of that year. One week later, on October 11 in the basement of 14 Wall Street, 52 banks participated in the first exchange.

On its first day, the Clearing House exchanged checks worth $22.6 million. Within 20 years, the average daily clearing topped $100 million. Today, the average is in excess of $20 billion.

The formation of the New York Clearing House brought order to what had been a tangled web of exchanges. Specie certificates soon replaced gold as the means of settling balances at the Clearing House, further simplifying the process. Once Clearing House certificates were exchanged for gold deposited at member banks, porters encountered fewer of the dangers they had faced previously while transporting bags of gold from bank to bank. Certificates also relieved the strain on the bank’s cash flow, thus reducing the likelihood of a run on deposits. Requirements placed on member banks–weekly audits, minimum reserve levels and daily settlement of balances–further assured more ordered, efficient exchanges.

Calming the panics

Between 1853 and 1913, the nation experienced rapid economic expansion as well as ten financial panics. One of the Clearing House’s first challenges was the panic of 1857. When the panic began, leaders of the member banks met and devised a plan that would shorten the duration of the panic–and more importantly, maintain public confidence in the banking system. When specie payments were suspended, the Clearing House issued loan certificates that could be used to settle accounts. Known as Clearing House Loan Certificates, they were, in effect, quasi-currency, backed not by gold but by discounted county and state bank notes held by member banks. Bearing the words “Payable Through the Clearing House,” a Clearing House Loan Certificate was the joint liability of all the member banks, and thus, in lieu of specie, a most secure form of payment.

The certificates appeared in smaller denominations during the panic of 1873, and continued to be used as a substitute currency among the member banks for settlement purposes during panics in subsequent decades, including the Panic of 1893. Although they represented a potential violation of federal law against privately issued currencies, these certificates, as a contemporary observer noted, “performed so valuable a service…in moving the crops and keeping business machinery in motion, that the government…wisely forbore to prosecute.”

In 1913, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act, thus creating an independent, federal clearing system modeled on the many private clearing houses that had sprung up across America. The new monetary system, with its stringent audits and minimum reserve standards, assumed the role that clearing houses had played in offsetting the nation’s fears of future panics.

Source Wikipedia

Florida clearing house certificates are all extremely RARE

Recent Articles

- Browse Videos of Florida’s Historical Towns and Banks

- Florida Currency Museum Open Showcasing The William Youngerman Collection

- State of Florida Civil War Currency

- Recent Acquisitions

- Mr. and Mrs. Youngerman attend the inagural “The Value of Money” exhibit

Notes & Currency

- 18__ Fernandina $3 Obsolete Note

- 1882 $50 Jacksonville Note Charter #3869

- 1902 $10 Punta Gorda Note Charter #10512

- 1882 $5 Palatka Note Charter #3223

- 1902 $5 Key West Note Charter #7942